The Way of Zen — Part 3

Thoughts and musings from reading The Way of Zen by Alan Watts.

The Tao is an indefinable process of the world, the “Way of life”.

A famous quote, one I’ve found very useful in reminding myself of this undefinable nature:

“The Tao which can be spoken is not eternal Tao”

Watts articulates an important division between the concepts of Tao and God. God produces the world by making but the Tao produces the world by not making. Another way of expressing “not making” is the term growing. When something is made, it is separate parts formed together. Yet when something is grown, it stems from a common source and emerges outward as a seamlessly unified whole.

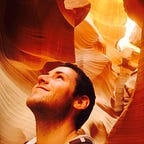

This brings to mind a natural process. Images of a tree, a branching river, or a fractal. These resonate with me more than the idea of this Universe being made, constructed. How could it be constructed? Constructed from what? What parts? By whom? A natural process of becoming, like a tree growing from the ground, is much more resonant.

Of course, just because something is natural does not mean it is good, or true, but in this context, it does fit much better than any idea of structure coming from without instead of within.

According to Watts, the Chinese mind would agree and would have a difficult time making sense of the Universe being made or constructed.

Instead, this universe is a process, and in the comparison to a tree, ideas of the universe being alive in some sense come to mind. An evolving organism, a process that has certain patterns, an unknowable entity that can perhaps help us to know.

“The great Tao flows everywhere,

To the left and to the right”

Reading this section frequently brought to mind the ideas and images I recently expressed in this poem. “The flow goes all directions” being just one of the lines.

This view of an essentially unknowable Tao conflicts with our ordinary relationship to knowledge in the West. God is the all-knowing, omniscient. Knowing means having control, so God is also omnipotent. Knowledge is power. Control.

The essentially mysterious nature of this concept of the Tao is foreign to us. The Tao has no part in control or in helping one control. The desire to control is at the base of much of our human nature, to control ourselves and the world around us. This unknowable, uncontrollable, and non-controlling force is therefore difficult to grasp or relate to.

We are also constantly doing, yet the Tao is the absence of doing. Not making.

Just as we can’t utilize our peripheral vision without relaxing the central vision, or see the whole scene lit by the floodlight without ignoring the narrow beam of our flashlight, we cannot “do nothing” while trying to do something. We can’t “not know” while trying to know.

Watts refers to the state of mind necessary to relate to the Tao as “non-graspingness” of mind.

Lao-Tzu, the originator of Taoism, said “the perfect man employs his mind as a mirror. It grasps nothing; it refuses nothing. It receives, but does not keep.”

This reminds me of an instruction sometimes used in the Waking Up meditation app by Sam Harris, to let your mind be like a mirror, reflecting perfectly that which is in front of it but never itself changing.

The Taoists speak negatively about the values of knowledge and cleverness that are so often lauded in the West. Not knowing is most intimate. Not knowing is the closest, most real form of experience.

It is in our knowledge, our cleverness, our concepts that we deviate from the natural order, or process of the universe, the Tao.

I struggle with this as someone who greatly admires and values knowledge and intelligence, yet Watts attempts to add nuance to this view in saying that the Taoists are not advocating for ignorance but instead a natural flow of knowledge and intellect. To stop trying, because it is in our efforts that we so often go astray and become deluded. I’ve heard Taoism describes as the Art of Not Trying, which seems to fit here. I do feel as though the reliance on the natural order and impulses of things in an ultimate sense is too narrow, but as written about on Day 2, when balanced with some order and structure (like Confucianism) not knowing can be seen in a more reasonable light.

I often struggle with being averse to a concept or idea because I try to apply it too broadly. A practice or concept can have great value in one specific context without being right for every situation. In the same way, I think the art of not trying, of not knowing, while perhaps not wholly sufficient for a prosperous world, is likely very well suited for personal enlightenment. Or for adding balance to life, breaking up the ceaseless stream of doing and knowing that characterizes the standard human mind.

Even if it is just for 10 or 20 minutes of meditation each day, the practice of not knowing can be extraordinarily valuable and liberating.

Continue Reading: The Way of Zen — Part 4